Field Experience on the Thai–Cambodian Border, 1979

The year was 1979. In October, I braved the streets of Bangkok, Thailand at five o’clock in the morning to get on a volunteer bus bound for the Thai–Cambodian border. Our destination was Sakeo, a newly established refugee camp sheltering 30,000 sick and dying Cambodian displaced people.

The camp sprawled across a large rice field. Because it was the rainy season, there was thick mud everywhere and rows of blue tarpaulins stamped with UNHCR logos. A so-called “hospital” occupied one corner of the encampment, made up of several large tents hastily erected by volunteer organizations. There were few trained staff or expatriate presence. The stench of excrement, death, and human suffering overwhelmed me.

I was only 23 years old, utterly unprepared for what lay ahead. Yet every time I reached a breaking point, I found renewed motivation in the urgency and desperation of those I was trying to help.

In the beginning, I volunteered in the tuberculosis ward, which was just a large tent attached to the International Rescue Committee. I had the honor of being trained over a few days by the Medical Missionary Sisters, a group of nuns from the United States.

My training consisted of rudimentary nursing skills: giving injections, carrying water, applying medical bandages, and setting up IVs. For about a month, this became my daily work.

Early on, a UN reufgee camp coordinator suggested I return to Bangkok to sign up formally with the International Rescue Committee, an NGO. I did so and was hired on the spot, returning quickly to the Sakheo camp.

Addressing Deficiency Diseases

At one point, someone learned that I had training in nutrition. They approached me because there was an apparent outbreak of a thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency disease in the camp. This was unsurprising: the population arriving from Khmer Rouge–controlled areas inside Cambodia had endured prolonged malnutrition and starvation under Pol Pot, and the food rations at Sakeo were grossly inadequate.

I examined the food being distributed and discovered it lacked sufficient protein and particularly B vitamins, causing deficiencies that were manifesting as disease. I recommended adding mung beans to the rations. Once implemented, with such a simple intervention, we saw a rapid improvement in the health of many refugees, and several deficiency syndromes began to disappear.

Discovering Food Distribution Inequities

What this article explores formed the basis of my later master’s thesis, “The Use of Food as a Weapon.”

Through my translator, I began receiving complaints from refugees across the camp that they were not receiving their proper food rations at the distribution points. To investigate, I brought scales, set up a table, and—together with translators—began weighing the food voluntarily as refugees exited the distribution site.

Each person was supposed to receive specific gram amounts of rice, meat, mung beans, and vegetables. But after a week or two, it became clear that there were major discrepancies: some people were receiving more than the allotted amount, and some much less.

Naively, as a 23-year-old, just fresh out of my university in the  U.S., I set up public weighing stations and posted the expected ration amounts on a board, so people could check whether their distribution matched the standard.

U.S., I set up public weighing stations and posted the expected ration amounts on a board, so people could check whether their distribution matched the standard.

Uncovering Coercion by the Khmer Rouge

I soon learned that my actions had unintentionally disrupted a covert power structure within the camp. The Khmer Rouge, still active among the refugees, were manipulating food distribution to coerce people to return to Cambodia and submit to Pol Pot’s authority. Those who complied received extra food; those who resisted received less or none.

Rumors of this circulated quickly. Not long after, I was summoned by the UN head of the camp to attend a meeting with the “refugee leadership”—in reality, Khmer Rouge operatives and former enforcers. The topic was this “major food distribution problem.”

As I walked to the meeting, my knees were shaking. I remember thinking, “Oh my God… what have I done?”

The Confrontation

As I walked into the tent, I saw a group of four or five men, the head of the UN office seated at the front, and a few others gathered around. I took a seat and immediately noticed the serious expression on the UN head’s face. It was clear that the situation was grave.

The Khmer Rouge representatives expressed their displeasure at the UN’s control over the food distribution points. They wanted to regain authority over the rationing system. Fortunately for me—and for the refugees—the head of the UNHCR office was exceptionally firm. He declared that control over food distribution would not be relinquished, as the food was provided by UNHCR and must be distributed equitably.

During the meeting, they asked about what was my role. I sat there uncomfortably, only to hear the UNHCR leader announce that I was now “in charge” of food distribution. Well, this was news to me, but apparently, my job had just changed.

Unexpected Negotiation

After the meeting, the Khmer Rouge representatives approached me. My heart sank andI thought, “This is it — I won’t survive this new role.”

But to my surprise, they asked for extra rice for weddings, explaining that many young people were marrying after years of prohibition under the Khmer Rouge. Relieved, I agreed to arrange extra rice allocations for wedding celebrations, which helped defuse tensions and built a tenuous rapport.

Scaling Up the System

The next phase was to expand the weighing stations across all food distribution points. We posted clear boards showing exact ration weights per person, enabling refugees to verify whether they were receiving their proper share.

A few months later, when the camp was preparing to move, the Khmer Rouge leadership could only coerce less than one-third of the population to return to the border. By shifting control to transparent, neutral distribution mechanisms, we had undermined their power and protected the majority of refugees who remained.

This simple innovation became a systematic new process adopted by the UN in the 16 refugee camps across Thailand in 1980. We replicated the weighing stations and ration boards, giving people the right to know their entitlements and receive adequate food. Then, I was hired by the UN, and we expanded this practice to refugee camps all over the world. I had the honor of working with UNHCR for thirty years in numerous countries afterward, helping develop guidelines and manuals to institutionalize equitable food distribution systems globally.

Entitlement & Moral Responsibility

I share this story, learned nearly 50 years ago, because today we are again facing a dangerous trend of using food as a tool of coercion. In several contexts, food aid is being blocked or manipulated to control civilian populations, undermining the principles of human rights that humanitarian actors fought to establish decades ago.

The concept of entitlement is central to any aid program. Food and health care are not favors—they are human rights essential to survival. When entitlement is stripped away by those in power—whether through guns or the lingering trauma of past violence—a profound moral disequilibrium is created. Our failure to uphold these principles represents a corrosion of obvious ethi cal standards.

cal standards.

Over the years, the UN — especially the World Food Programme — developed extensive tools, kits, and guidelines to uphold these principles. Yet too often, these manuals gather dust on shelves while oversight and neutrality waver on the ground.

Ultimately, the neutrality of humanitarian agencies and their ability to ”hold power—not yield it to armed actors—“ remains the cornerstone of equitable food distribution. In recent years, we’ve witnessed how corrupted access to food can become when neutrality erodes.

We often say, “Let’s learn from our past mistakes.” This story is a reminder that transparency, entitlement, and moral clarity in humanitarian aid are not abstract ideals—they are lifesaving practices.

- – Angela Berry-Koch, Former UNHCR Senior Nutrition Adviser, currently faculty at Psychiatry Redefined and contributor to Hunger Notes, 12 Oct. 2025

The report also reports how: “disrupted services and disease outbreaks compounded by environmental change can threaten global health security, putting people at risk of health hazards both in countries where they occur and across borders.”

The report also reports how: “disrupted services and disease outbreaks compounded by environmental change can threaten global health security, putting people at risk of health hazards both in countries where they occur and across borders.”

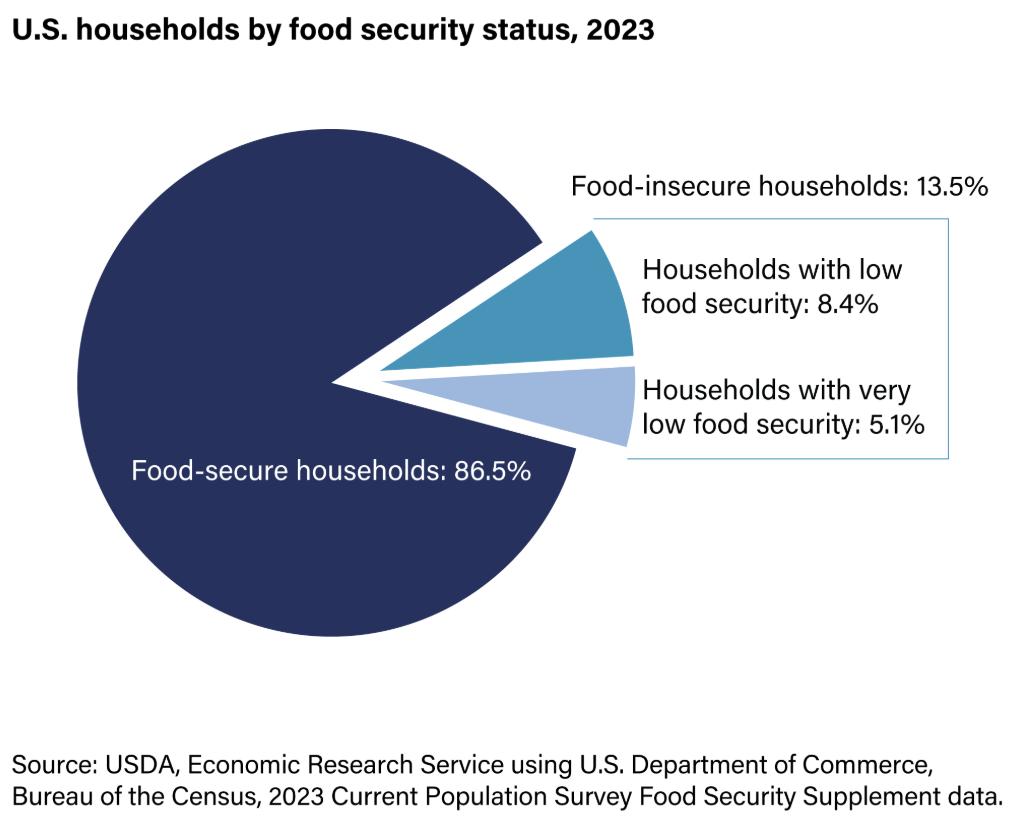

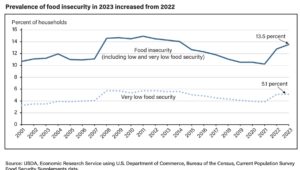

research experts are arguing that the cancellation of this annual survey will result in the loss of a significant data source that is used to inform policy on how to combat food insecurity in the U.S.. For example, Bread for the World issued a press release urging USDA to reverse the decision. They argued that the survey/report has been foundational for understanding how families experience food insecurity, especially children, and for making evidence-based policy decisions. The Food Research and Action Center criticized USDA’s decision as “shortsighted” and warned that eliminating the report hides the struggles of millions of families. They emphasized the importance of data in assessing policy impacts (e.g. SNAP cuts).

research experts are arguing that the cancellation of this annual survey will result in the loss of a significant data source that is used to inform policy on how to combat food insecurity in the U.S.. For example, Bread for the World issued a press release urging USDA to reverse the decision. They argued that the survey/report has been foundational for understanding how families experience food insecurity, especially children, and for making evidence-based policy decisions. The Food Research and Action Center criticized USDA’s decision as “shortsighted” and warned that eliminating the report hides the struggles of millions of families. They emphasized the importance of data in assessing policy impacts (e.g. SNAP cuts).

commendations, including a Presidential Meritorious Service Award. But those who worked alongside him often cited his field instincts and personal courage. Whether in Mogadishu, Kigali, or Kinshasa, he pressed the U.S. government to act decisively and compassionately, and he mentored a generation of younger humanitarian professionals who today carry forward his legacy.

commendations, including a Presidential Meritorious Service Award. But those who worked alongside him often cited his field instincts and personal courage. Whether in Mogadishu, Kigali, or Kinshasa, he pressed the U.S. government to act decisively and compassionately, and he mentored a generation of younger humanitarian professionals who today carry forward his legacy.