How Did the Debt Crisis Come About? What Was Its Impact on Poor Countries?

The debt crisis came about in two ways, through private sector lending and through the lending by the international financial institutions (see box).

Private Sector

The international debt crisis became apparent in 1982 when Mexico announced it could not pay its foreign debt, sending shock waves throughout the international financial community as creditors feared that other countries would do the same.

A key aspect of the crisis began in 1973 when the members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) quadrupled the price of oil and invested their excess money in commercial banks. The banks, seeking investments for their new funds, made loans to developing countries, often without appropriately evaluating the loan requests or monitoring how the loans were used.

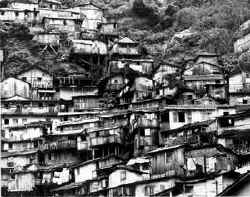

|

Refugee children in Uganda. Protracted internal conflict has taken its toll on many poor countries, such as Uganda. Nonetheless, repayment of debts must continue, according to the requirements of international lenders. |

In fact, due to irresponsible practices of creditor as well as debtor governments, much of the money borrowed was spent on programs that did not benefit the poor--armaments, large scale development projects, and private projects benefiting government officials and a small elite. The 1973 oil price increase also had the effect of triggering inflation in the United States and other industrialized countries.

In 1979, OPEC raised the price of oil a second time. Meanwhile, the United States adopted extremely tight monetary policies to reduce inflation, producing a domestic recession. The combined impact of the rising price of fuel and rising interest rates led to a worldwide recession.

Developing countries were hurt the most. Their exports declined as the domestic cost of production rose and the major importers reduced their purchase of goods from overseas. Latin American governments, which had taken out loans from commercial banks at floating interest, (rates that vary according to the current market interest rate) saw the interest on their debt skyrocket. African governments, reacting to the worldwide collapse in commodity prices, borrowed heavily from other governments and multilateral banks at both market interest rates and concessional (very low) rates. When Mexico finally announced that it could not pay its foreign debt, the international financial system appeared on the brink of collapse. The world's major creditors acted to save the commercial banks and the world economy.

Impact in the South

The existence of debt has both social and financial costs.

Heavily indebted poor countries have higher rates of infant mortality, disease, illiteracy, and malnutrition than other countries in the developing world, according to the UN Development Program (UNDP).

Six out of seven heavily indebted poor countries in Africa pay more in debt service (i.e., interest and principal repayments) than the total amount of money needed to achieve major progress against malnutrition, preventable disease, illiteracy, and child mortality before the year 2000. If governments invested in human development rather than debt repayments, an estimated 3 million children would live beyond their fifth birthday and a million cases of malnutrition would be avoided. The UNDP estimates that sub-Saharan African governments transfer to Northern creditors four times what they spend on the health of their people (Human Development Report, 1997). On the financial side, heavy indebtedness is a signal to the world financial community that the country is an investment risk, that it is unwilling or unable to pay its debt. As a result, impoverished countries are either cut off from the international financial markets or pay more for credit. The UNDP estimates that in the 1980s, the interest rates for poor countries were four times higher than for the rich countries due to inferior credit ratings and the expectation of national currency depreciations. Another cost of debt is the absence of infrastructure such as roads, schools, or health facilities that could both fight poverty and create the conditions for more economic growth. A different type of cost is associated with the time civil servants spend negotiating debt repayments. Oxfam International estimates there have been over 8,000 debt negotiations for Africa since 1980.

Heavily indebted countries face enormous pressure to generate foreign exchange in order to pay their debt service and purchase essential imports. The international financial institutions often offer financial assistance to countries in this situation and use their leverage to compel the countries to accept structural adjustment and stabilization policies. These structural adjustment policies (SAPs) and the austerity measures associated with them can have a strongly negative impact on the poor, both initially and for extended periods.

|

These dwellings in Honduras were almost certainly destroyed by Hurricane Mitch. Many poor developing countries face major problems in addition to high levels of debt, such as drought, reconstruction after natural disasters, and internal and external conflict. |

SAPs are designed to: I ) Stabilize faltering economies by reducing inflation and correcting the balance of payments; and, 2) Increase growth by making economies more productive and efficient and by opening them to market forces.

- Major elements in structural adjustment programs typically include:

- Raising taxes to increase government revenue and balance the budget

- Eliminating price and interest rate controls

- Reducing the size and scope of government and privatizing state-owned enterprises

- Reducing tariffs and other restrictions on foreign trade

- Reducing regulations on businesses and on capital flows to encourage local and foreign investment.

Although SAPs may help a country become more competitive in the global arena, they can severely harm the poor. This happens when:

- Social expenditures (especially for health, education, and welfare) are cut back in order to meet targets for reducing fiscal deficits

- Public sector employees are dismissed in government down-sizings without retraining or other economic opportunities

- Local companies close in the face of competition from abroad

- New investment is slow and does not create jobs at the rate expected.

SAPs can also create an environment that values global competition above all else, resulting in lower wages and worsening labor conditions for workers. Deregulation of labor markets can result in situations where workers cannot exercise their rights and local entrepreneurs and multinational corporations maximize their profits by operating sweatshops. Women and children, the majority of sweatshop workers, are hurt the most by starvation wages, long hours, and unsafe or unsanitary conditions.

SAPs are based on economic theories considered universally applicable, and thus are often applied uniformly. Yet, the specifics of the timing and sequencing of SAPs may not adequately take into account a country's political and institutional culture or its ability to absorb the adjustments. Governments are then forced to decide which public sectors to cut and which to save. Unfortunately, the poor and the vulnerable are the ones least able to protect themselves in this process.

STRUCTURAL ADJUSTMENT IN ZAMBIA In Zambia Annual per capita income is US $350; 80 percent of the population lives in absolute poverty; a recent drought has devastated the country; and HIV is a growing epidemic. Positive aspects of SAPS:

Negative aspects of SAPs:

|

Debt and structural adjustment policies can harm the environment. When countries need to generate more foreign exchange to service their debt, they increase exports. But because many developing countries depend on exports such as logging, mining, or a single agricultural crop, there is a serious risk that they will exploit these resources in a way that will cause major damage to the environment. Unless effective programs of environmental protection are put in place, export orientation can have a devastating impact on the land and its people.

CIDSE (International Cooperation for Development and Solidarity), is a network which brings together 16 Catholic development organizations located in Europe, North America, and New Zealand. Caritas International is a network of 146 national relief, development, and social service organizations. This article is adapted from their publication, "Putting Life Before Debt."

copyright